Pandemic Times: Nothing New Under the Venezuelan Sky

- by Manuel Vásquez-Ortega

- 23 may 2020

- 18 Min. de lectura

[Versión en español más abajo]

Originally published in Tráfico Visual on May 11, 2020

(…) The plague will deprive me of voices that are mine,

I will have to reinvent every gesture, every word

The sick boy (1886), Arturo Michelena

A mass grave in New York, more than 75,000 deaths in Europe, quarantine orders and the global emergency alert in the middle of 2020: these are facts that remind us once again that what was once archaic is not alien to contemporary times. With the appearance of a new pandemic that harasses humanity, the international panorama increases in complexity and contradictions to bring us closer to the frequent medieval references of the plague, meanwhile, we narrate individually our own stories of isolation, worry, fear of the other and scarcity of food in the tragicomic environment of a future seen from the Decameron of our present times, in which (as in the creation of Bocaccio) despite death, love, human intelligence and fortune continue to exist.

I

Along with Ebola, avian influenza, Zika and chikungunya, the new coronavirus (COVID-19) joins the list of massive diseases with a current global presence, the infections in many of the countries to which it has reached being unexpected and unprecedented. However, pandemics are not a new topic for Venezuela: if we briefly review history, we can find episodes such as the smallpox outbreak of 1580 which exterminated a large part of the Caracas indigenous people, the nineteenth-century tuberculosis outbreak and the continuous waves of the bubonic plague between 1908 and 1919, which happened close to the influenza outbreak that killed 1% of the population of the capital and the spread of malaria, to count just a few. All fought, many won, the current century shows that the great achievements of a State with the goal to progress have been left behind, and far from us is the ideal of a modern individual, "not only as a free economic agent ... but also as an immune body.” (Preciado, 2020).

For a long time, calamity has been a part of the Venezuelan present reality, therefore, with the return of epidemics to local territory, revisiting and resignifying images of history is made possible from the premise, that “what all images can do is represent other images.” (Foster, 2001), iconographies that are tied to referents or “real things in the world”. In our case, a fragment in continuous erosion in which - as in obscurantism - pandemic and war overlap in the daily life of decadence, knowing that, from medieval iconography, plagues and struggles have shared similarities that allow us to address them from that which makes them common: their proximity to death, in which decomposition, skeletons, subjects and animals configure the horizon of a city that closes its doors to chaos, even when the disease is already inside.

In these representations, horses push carts full of corpses, transport sick people, or are driven by riders who purvey both salvation and misfortune. However, in the midst of this referential context, an equestrian figure appears differently: Miguel von Dangel's Monument (1975–1985) stands on its hind legs to speak to us from the ambivalence of resistance to falling, of the battle or the loss, of wealth and deposition, while his discourse breaks with the existing time line between the central throne of 'The triumph of death' (Unknown author, Palazzo Abatellis, 1446) and Bolívar's victorious representations of his white beast created by Tito Salas. If the latter has painted to teach history and exalt the great Venezuelan men, contrary to and from a timeless place, von Dangel's taxidermic sculpture breaks away from the patriotic connotations and idolatries to become a monument of national tragedy, marked for the belligerence, the oil and the absence of a tamer.

Monument (1975–1985), Miguel von Dangel

II

Between equines and the dead, an animal flees without knowing that it carries the plague with it. This is how in the 20th century the bubonic plague arrived by boat as an unwanted passenger to Venezuela, living in black rats and transmitted through their fleas. By then, the government of Cipriano Castro managed to control (moderately) the health emergency in the port of La Guaira, after a quarantine decree and taking drastic measures, positioning itself as a clear episode of immunology in the history of our 'sovereign society ', that which according to Foucault, “manages and maximizes the life of the populations in terms of national interest.” (Preciado, 2020).

This act demonstrates that, as “all living (and therefore mortal) bodies are the central object of all politics” (idem), in times of pandemic, biopower more than ever becomes immunological, that is: it recognizes foreign elements and emits an answer, through the “establishment of a hierarchy between those bodies exempt from taxes (those who are considered immune) and those that the community perceives as potentially dangerous, and therefore, excluded in an act of protection” (idem). In this way, the management of the biological processes of populations is inevitably linked to necropolitical approaches, a way in which to kill or to let live makes us question the limits of the sovereignty of a territory.

In her series Experiment with rat # 4 (2012), Dianora Pérez-Montilla reflects and explores about these limits, the interstices between biopolitics (the control of existence through life and its improvements) and necropolitics (the control of life through death and its possibilities), experimentation in which the artist manipulates, opens and delves into the corpse of a rodent through macro-photography, a strategy with which she registers an unorthodox method of taxidermy by means of a journal and archive process. “In what concrete conditions is that power to kill, to let live or to expose oneself to death exercised? Who is the subject of this right?”, asks Mbembe (2001). The visual products of Pérez-Montilla's essay could give him an answer, turning into representations of recognizable situations for Venezuelans before a State that "has managed, protected and cultivated life coextensive with the sovereign right to kill" (ditto).

Experiment with rat #4 (2012), Dianora Pérez–Montilla

The fictionalized notion of an enemy is also present in the theories of Mbembe, who affirms - and thereby reaffirms Foucault - that the elimination of the opponent is in many cases extended in time and pain mainly to satisfy a multitude, a process in which a “new cultural sensibility arises in which killing the enemy of the State becomes the prolongation of a game (…) –where– more intimate, horrible and slow forms of cruelty appear” (2011). As an emblematic example and crucial image of our history, Miranda in the Carraca (1896) by Arturo Michelena portrays the controversial scene of a universal man, illustrious, and yet, branded as a traitor (therefore, enemy of power) after signing the capitulation of the Patriot Army in 1812. Condemned to confinement and oblivion for the rest of his life, in a punishment as intense as any other, the despair of the hero is reflected in the oil on canvas by Michelena and turned into an inescapable reference to myth and true narration of the hero, in an image in which the “secular anxiety that painfully concerns our conflictive relationship with the world and with the foreigner” is concentrated (Pérez Oramas, 2000). After a long and painful agony, Francisco de Miranda died in prison in 1816, being buried in a communal grave in the Arsenal de la Carraca cemetery.

Miranda en la Carraca (1896), Arturo Michelena

Confined in a different way, in 2013, Joao Dos Santos Correia remained kidnapped for 11 months and 3 days, a time of confinement “in a cell 2 meters high and 3 meters wide in which they placed a bed that hardly fit.” (Pérez Daza, online). The case became famous after his release, and comes to us turned into more than just a news article, to speak to us in terms of 'reality' through the Bunker (2013) of Juan Toro, under the idea that "something becomes real - for those who are in other places following it as «news» - (only) when being photographed” (Sontag, 2003).

In Toro’s series of images, something silent disturbs and bothers; this is his intention: the exhibition of an intact crime scene, in the most frank and heartbreaking way possible, from ruins and shreds, indispensable rubble to "rediscover the exact shape of the vestiges on which the social building rests” (Bourriaud, 2015). The intention to rescue memory is defended by Benjamin, who highlights the artist's duty to pay a moral debt, because revisiting the story's account is doing justice to the vanquished who lie, in disorder, “within a tingling mass grave of semi-erased stories, insinuated futures, of potential companies”.

Bunker (2013), Juan Toro

III

The mandatory isolation imposed in many countries after COVID-19 is, apparently, one of the most efficient ways to keep us safe in times of contagion and mortality. However, at the same time, it shows:

"the inability of some states or regions to prepare in advance, the strengthening of national policies and the closing of borders, and the arrival of businessmen eager to capitalize on global suffering, all bearing witness to the speed with which radical inequality, which includes nationalism, white supremacy, violence against women (…) find ways to reproduce and strengthen their powers within pandemic zones” (Judith Butler, 2020).

Will it ever be safe to ‘get out’ of confinement? Can we find a safe place abroad? For some people, especially women, the fear of becoming infected is no greater than that of staying at home, and this is because, in a recent UN report, it was warned that in this emergency context the risks of violence, especially domestic, against women and girls increase. Now, what does it mean to protest suffering, as opposed to just acknowledging it? In the video The wounded little wolf (El lobito herido) (1994), Sandra Vivas presents a soap opera 'promo', a direct reference - almost - to The Wounded She-wolf (La Loba Herida), a Venezuelan fiction from '92 that over 214 chapters narrates the misadventures of rape within a family circle. In the work, contrary to the generalization of these cases, Vivas assumes the leading role of an aggressive and unbalanced woman who mistreats her docile companion. Because "the desire for images that show suffering bodies is almost as strong as the desire for those that show naked bodies" (Sontag, 2003), in this way, Sandra Vivas not only establishes a critical position regarding domestic violence , but also questions the roles of men and women continually portrayed and broadcast by the supremacy of the media, hidden under romanticisms that promise "to reach a thousand stars with the hands, to see our sky more than illuminated and walk under the same footprint" (excerpt from the The Wounded She-wolf).

The wounded little wolf (1994), Sandra Vivas

Far from any touch (even the song metaphor), our hands are subject to new guidelines: do not bring them to your face, wash them with soap constantly, keep physical distance from other people. Guidelines compiled in a new epidemic term of the XXI century, the Social Distance. And, when - perhaps very hastily - Giorgio Agamben affirmed that the fear of contagion from others is imposed as a way of restricting freedoms, he also expresses the fear that the State of Exception will become a normalized situation, that the mandatory will be natural, that the emergency will be a day-to-day affair. That the other, the stranger, the foreigner, is a potential carrier of the virus. Thus, uncertainty becomes a tangible presence of today, in which reflection is a constant practice for many and a privilege for others. In all cases, however, isolation is mandatory.

Light behind my entwined branches (1926), Armando Reverón

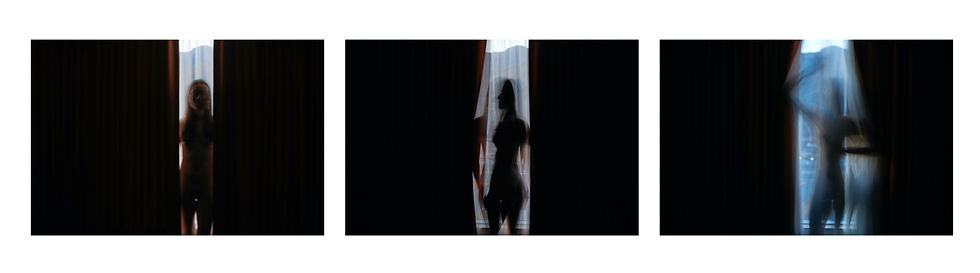

Although the figure of the anchorite in the Venezuelan arts is marked by Armando Reverón and his retirement in El Castillete, several creators have delved into the action of abstracting into self-exile. This is how, although far from any Reveronian eccentricism, Suwon Lee poses a trip to her own interior in the Korea series (2019), a look at her own emotionality, without forgetting the inevitable relationship with the space that surrounds her. In this way, the physical-material-tangible of an interior space dialogues in photographic images with representations of the intangible, understood through Lee's lens, in which a characteristic (Reveronian?) exploration of her work prevails over any intention: the presence, variation and movement of light as a discursive resource. In this intimate universe shown through the self-portrait, Suwon Lee exposes one of the many faces of immigration, that of loneliness and its darkness, as well as the inner search for something uncertain but existing in all.

Korea (2019), Suwon Lee

Finally, the interior / exterior relationship of the universal and the vernacular in Venezuela becomes more complex in tune and parallelism with the global tragedy, but still far from visible improvements. We thus return to the unfortunate figure of the country's history which "embodies the possibility (or example) of having been in harmony with the context of its world" (Francisco de Miranda). This image of dramatic difference which seems to exist between “the certainty of being contemporary at a global time and the will to make this certainty fertilize in the territory and in the time of the vernacular” (Pérez Oramas, 2000), is appropriated and reinterpreted by Rafael Arteaga in his Study of Blackout series (2019) in which the long sadness of the hero acquires a new moment of enunciation: the calamity of a present in which the pandemic times seem to be nothing new - neither insurmountable - under the Venezuelan sky. Still, it is decisive for the future course of our complex history.

Study of Blackout (2019),

Rafael Arteaga

References:

BOURRIAUD, Nicolas (2015): La Exforma, Madrid, Adriana Hidalgo.

BUTLER, Judith (2020): Capitalism has its limits. In: Wuhan Soup, Aspo.

FOSTER, Hal (2001): The return of the real, Madrid, Akal.

MBEMBE, Achille (2001): Necropolitics, Spain, Melusina.

PÉREZ ORAMAS, Luis Enrique (2000): Apostille for the end of the century. In: Venezuela XX century, visions and testimonies, Caracas, Fundación Polar.

PÉREZ DAZA, (2018): Photography against oblivion. In: La ONG (http://www.laong.org/el-bunker-fotografia-contra-el-olvido-johanna-perez-daza/), (online).

PRECIADO, Paul B. (2020): Learning from the virus. In: Wuhan Soup, Aspo.

STRAKA, Tomás (2020): Pandemic and memory. At: Prodavinci (https://prodavinci.com/pandemia-y-memoria), (online).

SONTAG, Susan (2003): Regarding the pain of others, Madrid, Santillana.

[Versión en español]

Tiempos de pandemia: Nada nuevo bajo el cielo venezolano

por Manuel Vásquez-Ortega

(…) la peste me privará de voces que son mías,

tendré que reinventar cada ademán, cada palabra

Eugenio Montejo

Una fosa común en Nueva York, más de 75.000 muertes en Europa, órdenes de cuarentena y la alerta de emergencia mundial en pleno 2020, son hechos que nos recuerdan una vez más que lo arcaico no es una idea ajena a lo contemporáneo. Con la aparición de una nueva pandemia que hostiga a la humanidad, el panorama internacional aumenta en complejidad y contradicción para acercarnos a las frecuentes referencias medievales de la peste, mientras tanto, individualmente narramos nuestros propios relatos de aislamiento, preocupación, miedo al otro y escasez de alimentos en el ambiente tragicómico de un futuro visto desde el Decamerón de nuestra actualidad, en el que (como en la creación de Bocaccio) a pesar de la mortandad, el amor, la inteligencia humana y la fortuna continúan en existencia.

I

Acompañado del ébola, la gripe aviar, el zika y el chikungunya, el nuevo coronavirus (COVID-19) se une a la lista de padecimientos masivos de presencia actual, vistos como contagios de aparición sorpresiva e inédita en muchos de los países a los que han alcanzado; sin embargo, las pandemias no son un tema novedoso para Venezuela, pues en una breve revisión histórica podemos encontrar episodios como la viruela que en 1580 exterminó a gran parte de los Indios Caracas, la cúspide decimonónica de la tuberculosis y los continuos focos de peste bubónica entre 1908 y 1919, tiempos cercanos a la influenza que acabó con el 1% de la población de la capital y a la propagación de la malaria, por contar solo algunos. Combatidos todos, ganados muchos, el siglo en curso demuestra que atrás quedaron los grandes logros alcanzados por un Estado con miras en el progreso, y muy lejos de nosotros está el ideal de individuo moderno, “no sólo como agente (…) económico libre, sino también como cuerpo inmune” (Preciado, 2020).

Desde hace mucho, la calamidad es el presente venezolano, por ello, con el regreso de las epidemias a territorio local, revisitar y resignificar imágenes de la historia se hace posible desde una premisa, que “lo que todas las imágenes pueden hacer es representar otras imágenes” (Foster, 2001), iconografías que se atan a referentes o “cosas reales del mundo”. En nuestro caso, un fragmento en continua erosión en el que –como en el oscurantismo– pandemia y guerra se solapan en la cotidianidad de la decadencia, a sabiendas de que, desde la iconografía medieval, pestes y pugnas han compartido similitudes que permiten abordarlas desde aquello que las hace común: su cercanía con la muerte, en la que descomposición, esqueletos, sujetos y animales desahuciados configuran el horizonte de una ciudad que cierra sus puertas al caos, aun cuando la enfermedad ya está adentro.

En dichas representaciones, caballos empujan carretas llenas de cadáveres, trasladan enfermos, o son conducidos por jinetes que imparten tanto salvación como desgracia. No obstante, en medio de este contexto referencial, una figura ecuestre aparece de forma otra: el Monumento (1975–1985) de Miguel von Dangel se levanta en sus patas traseras para hablarnos desde la ambivalencia de la resistencia a la caída, de la batalla o la pérdida, de la riqueza y la deposición, mientras su discurso rompe con la línea temporal existente entre el jamelgo central de ‘El triunfo de la muerte’ (Autor desconocido, Palazzo Abatellis, 1446) y las victoriosas representaciones de Bolívar sobre su bestia blanca creadas por Tito Salas. Pues, si éste último ha pintado para enseñar la historia y exaltar los grandes hombres venezolanos, contrariamente y desde un lugar sin tiempo, la escultura taxidérmica de von Dangel se desprende de las connotaciones e idolatrías patrióticas para convertirse en monumento de la tragedia nacional, marcada por la beligerancia, el petróleo y la ausencia de un domador.

II

Entre equinos y finados, un animal huye sin saber que lleva la plaga consigo. Fue así como en el siglo XX la peste bubónica llega en barco como pasajera indeseada a Venezuela, alojada en las ratas negras y transmitida a través de sus pulgas. Para entonces, el gobierno de Cipriano Castro logra controlar (medianamente) la emergencia sanitaria en el puerto de La Guaira, tras un decreto de cuarentena y la toma de drásticas medidas, posicionándose como un claro episodio de inmunología en la historia de nuestra ‘sociedad soberana’, aquella que según Foucault “gestiona y maximiza la vida de las poblaciones en términos de interés nacional” (Preciado, 2020).

Este acto demuestra que, como “todo cuerpo vivo (y por tanto mortal) es el objeto central de toda política” (ídem), en tiempos de pandemia, el biopoder más que nunca se hace inmunológico, es decir: reconoce elementos ajenos y emite una respuesta, a través del “establecimiento de una jerarquía entre aquellos cuerpos exentos de tributos (los que son considerados inmunes) y aquellos que la comunidad percibe como potencialmente peligrosos, y por ende, excluidos en un acto de protección” (ídem). De esta forma, la gestión de los procesos biológicos de las poblaciones se vincula inevitablemente a planteamientos necropolíticos, una forma en la que hacer morir o dejar vivir nos hace cuestionar los límites propios de la soberanía de un territorio.

En su serie Experimento con Ratón #4 (2012), Dianora Pérez-Montilla reflexiona y tantea sobre estos límites, intersticios entre la biopolítica (el control de la existencia a través de la vida y sus mejoras) y la necropolítica (el control de la vida a través de la muerte y sus posibilidades), experimentación en la que la artista manipula, abre y hurga el cadáver de un roedor a través de la macro-fotografía, estrategia con la que registra un método de taxidermia poco ortodoxo por medio de un proceso de diario y archivo. “¿En qué condiciones concretas se ejerce ese poder de matar, de dejar vivir o de exponer a la muerte? ¿Quién es el sujeto de ese derecho?”, se pregunta Mbembe (2001). Las visuales productos del ensayo de Pérez-Montilla podrían darle respuesta, convertidas en representaciones de situaciones reconocibles para el venezolano ante un Estado que “ha gestionado, protegido y cultivado la vida de forma coextensiva con el derecho soberano de matar” (ídem).

La noción ficcionalizada de un enemigo se hace también presente en las teorías de Mbembe, quien afirma –y con ello reafirma a Foucault– que la eliminación del oponente es en muchos casos extendida en tiempo y dolor principalmente para satisfacer a una multitud, proceso en el que surge una “nueva sensibilidad cultural en la que matar al enemigo del Estado se convierte en la prolongación de un juego (…) –donde– aparecen formas de crueldad más íntimas, horribles y lentas” (2011). Como ejemplo emblemático e imagen crucial de nuestra historia, Miranda en la Carraca (1896) de Arturo Michelena retrata la polémica escena de un hombre universal, ilustre, y sin embargo, tildado de traidor (por ende, enemigo del poder) tras firmar la capitulación del Ejército Patriota en 1812. Condenado al confinamiento y al olvido por el resto de su vida, en un castigo tan intenso como cualquier otro, la desesperanza del prócer es plasmada en el óleo sobre lienzo de Michelena y convertida en referencia ineludible del mito y la narración verídica del héroe, en una imagen en la que se concentra la “ansiedad secular que concierne dolorosamente a nuestra conflictiva relación con el mundo y con el extranjero” (Pérez Oramas, 2000). Tras una larga y penosa agonía, Francisco de Miranda fallece en prisión en 1816, siendo enterrado en una tumba comunitaria en el cementerio del Arsenal de la Carraca.

Confinado de una forma diferente, en el 2013, Joao Dos Santos Correia permaneció secuestrado durante 11 meses y 3 días, tiempo de encierro “en una celda de 2 metros de alto y 3 de ancho en la que dispusieron una cama en la que difícilmente cabía” (Pérez Daza, en línea). El caso, mediático tras su liberación, llega a nosotros convertido en algo más que una noticia reporteril, para hablarnos en términos de ‘realidad’ a través del Bunker (2013) de Juan Toro, bajo la idea de que “algo se vuelve real –para los que están en otros lugares siguiéndolo como «noticia»– (solo) al ser fotografiado” (Sontag, 2003).

En la serie de imágenes de Toro, algo silencioso perturba e incomoda; de eso se trata su intención: la exposición de una escena de crimen intacta, de la forma más franca y desgarradora posible a partir de ruinas y jirones, escombros indispensables para “reencontrar la forma exacta de los vestigios sobre los cuales se apoya el edificio social” (Bourriaud, 2015). Intención de salvamiento de la memoria defendida por Benjamin, quien resalta el deber del artista de saldar una deuda moral, pues revisitar el relato de la historia es hacerle justicia a los vencidos que yacen, en desorden, “dentro de una fosa común hormigueante de relatos semiborrados, futuros insinuados, de sociedades en potencia”.

III

El aislamiento obligatorio impuesto en muchos países tras el COVID–19 es, al parecer, una de las formas más eficientes para mantenernos seguros en tiempos de contagio y mortandad. Sin embargo, al mismo tiempo, demuestra “la incapacidad de algunos estados o regiones para prepararse con anticipación, el refuerzo de las políticas nacionales y el cierre de las fronteras y la llegada de empresarios ansiosos por capitalizar el sufrimiento global, todos dan testimonio de la rapidez con la que la desigualdad radical, que incluye el nacionalismo, la supremacía blanca, la violencia contra las mujeres (…) encuentran formas de reproducir y fortalecer su poderes dentro de las zonas pandémicas” Judith Butler, 2020.

¿Será seguro algún día ‘salir’ del confinamiento? ¿Podremos encontrar un lugar a salvo en el exterior? Para algunas personas, en especial mujeres, el miedo a contagiarse no es mayor al de permanecer en su hogar, y es que, en un reciente informe de la ONU, se alertó que en este contexto de emergencia aumentan los riesgos de violencia contra las mujeres y las niñas, especialmente violencia doméstica. Ahora bien, ¿qué implica protestar por el sufrimiento, a diferencia de solo reconocerlo?

En el video El lobito herido (1994), Sandra Vivas presenta una ‘promo’ de telenovela, referencia –casi– directa de La Loba Herida, ficción venezolana del ‘92 que a lo largo de 214 capítulos narra las desventuras de una violación dentro de un círculo familiar. En la obra, contraria a la generalidad de los casos, Vivas asume el rol protagónico de una agresiva y desequilibrada mujer que maltrata a su dócil acompañante. Y es que “la apetencia por las imágenes que muestran cuerpos dolientes es casi tan viva como el deseo por las que muestran cuerpos desnudos” (Sontag, 2003), de esta forma, Sandra Vivas no solo establece una posición crítica respecto a la violencia doméstica, sino también cuestiona los roles de hombre y mujer continuamente respaldados y difundidos por la supremacía de los medios, escondidos bajo romanticismos que prometen “con las manos alcanzar mil estrellas, ver nuestro cielo más que iluminado y caminar bajo una misma huella” (extracto de la Loba Herida).

Lejos de cualquier tacto (incluso de la metáfora de la canción) nuestras manos están sometidas a nuevas directrices: no llevarlas a la cara, lavarlas con jabón constantemente, mantener distancia física de otras personas. Pautas recopiladas en un nuevo término epidémico del siglo XXI, el Distanciamiento Social. Y es que, cuando –tal vez muy apresuradamente– Giorgio Agamben afirmó que el temor a contagiarse de otros es impuesto como forma de restringir libertades, manifiesta también el temor de que el Estado de Excepción se convierta en una situación normalizada, que lo obligatorio sea natural, que la emergencia sea cotidiana. Que el otro, el extraño, el extranjero, sea un potencial portador del virus. Así, la incertidumbre se vuelve una presencia tangible en los días actuales, en los que la reflexión es una constante para muchos y un privilegio para otros. Para todos los casos, empero, el aislamiento es obligatorio.

Si bien la figura del anacoreta en las artes venezolanas es marcada por Armando Reverón y su retiro en El Castillete, varios creadores han profundizado en la acción de abstraerse en el autoexilio. Es así como, aunque lejos de cualquier excentricismo reveroniano, Suwon Lee plantea un viaje a su propio interior en la serie Corea (2019), una mirada a una emocionalidad propia, sin olvidar la relación inevitable con el espacio que la rodea. De esta manera, lo físico-material-tangible de un habitáculo dialoga en imágenes fotográficas con las representaciones de lo intangible, entendido desde el lente de Lee, en la que una exploración (¿reveroniana?) característica de su obra prevalece sobre cualquier intención: la presencia, variación y movimiento de la luz como recurso discursivo. En este universo íntimo mostrado a través del autorretrato, Suwon Lee expone una de las muchas caras de la inmigración, la de la soledad y su oscuridad, así como la búsqueda interior de algo incierto pero existente en todos.

Finalmente, la relación interior/exterior de lo universal y lo vernáculo de nuestro país se vuelve más compleja en sintonía y paralelismo con la tragedia mundial, pero aún lejos de mejoras visibles. Volvemos así a la desdichada figura de la historia patria que “encarna la posibilidad (o el ejemplo) de haber estado en armonía con el contexto de su mundo”, Francisco de Miranda. Imagen de la dramática diferencia que parece existir entre “la certeza de ser contemporáneos a un tiempo global y la voluntad de hacer fecundar dicha certeza en el territorio y en el tiempo de lo vernáculo” (Pérez Oramas, 2000), apropiada y reinterpretada por Rafael Arteaga en su serie Estudio sobre apagón (2019) en la que la larga tristeza del prócer adquiere un nuevo momento de enunciación: la calamidad de un presente en la que los periodos de pandemia parecen ser nada nuevo –tampoco insuperable– bajo el cielo venezolano, aun así, decisivos para el futuro curso de nuestra compleja historia.

Referencias:

BOURRIAUD, Nicolas (2015): La Exforma, Madrid, Adriana Hidalgo.

BUTLER, Judith (2020): El capitalismo tiene límites. En: Sopa de Wuhan, Aspo.

FOSTER, Hal (2001): El retorno de lo real, Madrid, Akal.

MBEMBE, Achille (2001): Necropolítica, España, Melusina.

PÉREZ ORAMAS, Luis Enrique (2000): Apostilla para fin de siglo. En: Venezuela Siglo XX, visiones y testimonios, Caracas, Fundación Polar.

PÉREZ DAZA, (2018): La fotografía contra el olvido. En: La ONG (http://www.laong.org/el-bunker-fotografia-contra-el-olvido-johanna-perez-daza/), (en línea).

PRECIADO, Paul B. (2020): Aprendiendo del virus. En: Sopa de Wuhan, Aspo.

STRAKA, Tomás (2020): Pandemia y memoria. En: Prodavinci (https://prodavinci.com/pandemia-y-memoria), (en línea).

SONTAG, Susan (2003): Ante el dolor de los demás, Madrid, Santillana.